A Cut Right Down The Middle

Throughout the end of 2021 and beginning of 2022, I’ve been writing, testing, rewriting and refining a new programming interface for AVS. This new and improved interface will set AVS free from it’s former home Winamp, and later Windows too. This post is a bit longer and will dive gradually and successively deeper into the important details while outlining the reasoning behind the decisions that shaped them.

Double Liberation #

AVS is a Winamp plugin, which means it only works when run through Winamp or other compatible players (such as Foobar2000 or XMPlay). One goal of this project is decoupling AVS from being “just” a plugin and turning it into a proper generic software library instead.

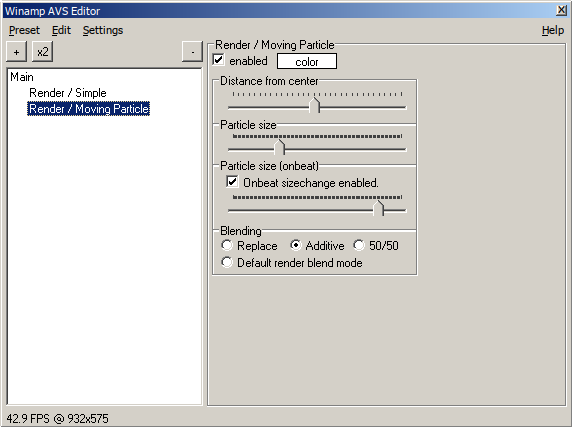

But when that is done, AVS’ UI for editing presets is still only written for Windows. You can tell by the homely early-2000’s look of the editor:

Note the familiar grey background color and menu bar.

Most UI systems are operating-system-specific and that’s okay — or at least we’ve come to terms with that. Rendering pretty visuals (what AVS is all about) on the other hand has very few OS-specific dependencies. It’s feasible to make the rendering part of AVS portable across operating systems. And I want to run AVS on Linux badly! But a builtin Windows-only UI stands squarely in the way of that. So it was clear to me that the UI has to be cut away from the core rendering engine of AVS and put into its own project. Still, AVS needs one or more UIs which must be able to read and edit the current preset. For that there needs to be a communication layer, an API.

AVS, the Winamp plugin, already has an API so Winamp can know about it and start it, send it sound data and ask for a visualization window with the resulting images. To decouple AVS from Winamp this API for rendering only needs a little bit of change to be more generic. That one is the basic API and I will talk about it in detail another time. To decouple AVS from Windows a much bigger and completely new section of the API needs to be created for UI interaction. This post will be about this part: the editor API.

A Unified Effect and Parameter Interface #

AVS presets are basically a list of effects that are run through sequentially, each operating on the output of the previous one to produce the final image. And there are a lot of effects in AVS, around 70. Each of them has some parameters for configuration, a median of 4 parameters, up to a maximum of 23. What complicates matters is that every effect defines its own specialized UI, and so has its own “private conversation” with it.

To separate AVS’ UI each of these conversations has to be cut open and handled through the editor API. It’s clear from the numbers that the API cannot accommodate each effect separately, it would be huge. The conclusion is that all effects and parameters need changing to follow a common unified pattern.

From the outside AVS effects need to be discoverable and their parameters too. The editor API has to answer the question “Which effects are available?” and “Which parameters does effect X have and what do they look like?”. This requires that all effects and all parameters have the same shape respectively. Then the API can just return lists of things with the same type.

The way effects are homogenized is by having them all inherit from a single base class, which is the C++ idiom for “common shape”. Inheritance1 fits because while effects have similar basic properties, they vary wildly in implementation. Parameters are the opposite, they all work more or less the same, but have a few distinct sub-types with differing properties: There are numeric values which have a minimum and maximum. There is a “select” type with a fixed set of possible options to choose from. And there are on/off switches, colors, strings, etc. So parameters are all instances of one single class with a lot of optional fields that are only used for some variants. This is a more C-ish idiom for this type of “common shape”.

“Effects” vs. “Components” #

In AVS and its API there is a distinction between a type of effect and an instance of that effect. A user chooses a type of effect to add, which then creates an instance of it and puts it into the preset. I decided to call the former “Effect” and the latter “Component”. Effects have static information like a name, a description, parameters, while Components have editable parameter values and can be moved around, copied and deleted etc. AVS has a fixed collection of Effects with static properties while presets consist of a list (actually, a tree) of editable Components.

Historically all of these used to be called “Render” inside the original AVS’ source code, which was doubly confusing. It used one word for two concepts and some effects don’t actually render anything at all.

Effect Information, Parameter Types and Preset Structure #

Now for a first glimpse into the editor API itself. For reasons of compiler interoperability explained in a previous post it cannot be a C++ API, so it’s all in C. If you want you can read the source API header file along with the rest. The core types are these three:

typedef struct { ... } AVS_Effect_Info;

typedef struct { ... } AVS_Parameter_Info;

enum AVS_Parameter_Type { ... };

where AVS_Effect_Info is the the metadata for one effect,

while AVS_Parameter_Info contains everything there is to know about a parameter,

and AVS_Parameter_Type lists all the parameter type variants mentioned above.

You can imagine an effect as a set of fixed attributes, such as name and description along with a list of parameters. These parameters each carry at least a name and a type, but often much more (such as minimum and maximum value, if it’s a number). I’m going to introduce a basic notation2 for effect metadata here. This is not API code, it’s just a better way to show the relationships between effects and parameters than the actual C structs and pointers. Let’s look at a made-up example effect with two parameters:

name: My Effect

description: Just an example effect.

handle: 123 # We'll get to this in a second

parameters:

- name: Parameter 1

type: int

min: 0 # Special 'min' & 'max' properties for 'int' type.

max: 100

- name: Parameter 2

type: string

This would describe an effect called “My Effect” along with two parameters: “Parameter 1”, which is an integer number that goes from 0 to 100 and “Parameter 2”, which is just a string. A component created from this effect may look like this:

effect: 123 # = My Effect

handle: 987654

parameter values:

Parameter 1: 5

Parameter 2: "hi there"

Object Handles #

Before I talk about some of the API functions, a.k.a. what you can do with effects, components and parameters, there is one small but important concept: Handles. Handles are one conventional way to keep the details of data structures out of an API. When handling even mildly complex structures through an API it is best to reduce the amount of information “known” to outside users. This is not out of secrecy (everything’s open-source anyway) but to keep the “contract” that is described by the API minimal. Otherwise, every little data structure change is an API change. Those should be kept to an absolute minimum, because every time it happens consumers of that API might have to be changed as well.

// AVS_Handle is from the basic API which the editor API builds on

typedef uint32_t AVS_Handle;

typedef uint32_t AVS_Effect_Handle;

typedef uint32_t AVS_Component_Handle;

typedef uint32_t AVS_Parameter_Handle;

As you can see the handles here are just fancy names for 32-bit unsigned numbers. They are arbitrary and their values don’t mean anything. They are not pointers to the objects (other APIs sometimes use their objects’ memory addresses as handles). The only required property is that they don’t change during their objects’ lifetimes. Effect- and parameter handles are currently determined at compile time. An AVS instance handle and components’ handles are determined when the respective objects are created.

These handles are what every function of the editor API expects as some part of their input. And if they need to return an object they return a handle referring to it. Armed with a handle to an effect, component or parameter it’s now a single API call for the user to retrieve that object’s details.

But isn’t AVS_Effect_Info a data structure?

How does that “keep implementation details out of the API”?

The answer is that the structs defined in the API header are used just for the API.

While the internal representation of effects and parameters may be very similar, they don’t have to match.

When you ask for an AVS_Effect_Info object from avs_component_effect()

you get one that was constructed from the appropriate fields of the internal Effect object,

and the same for AVS_Parameter_Info.

All these types of API objects are only created once when AVS loads and then kept around for reuse.

Editing AVS Presets #

Necessarily the editor API provides functions (or “endpoints” in API jargon) that users can call to actually, well, edit a preset.

Despite my efforts to keep the editor API minimal it has grown to a list of 31 functions, currently. Two of them are concerned with listing and inspecting effects. Ten functions handle preset component inspection and editing (moving, copying, deleting, etc.). The rest, almost two thirds of the API, handle parameter editing. These are mostly getters and setters for the various types parameters can have.

It would not be very useful to list and explain all the functions here,

the avs_editor.h header does a better job of that, as it should.

To edit a parameter in an existing preset one has to perform the following list of steps:

- Retrieve the root component of the preset with

avs_component_root(). - Walk over the preset component tree with

avs_component_children(). - Select the desired component’s handle (possibly with a helping combination of

avs_component_effect()andavs_effect_info()) - Iterate over the component’s parameters (which are listed in its effect’s

AVS_Effect_Infostruct) - Get the desired parameter’s type (by checking its info-struct’s

typeproperty) - Call the type-appropriate

avs_parameter_set_*()function (e.g.avs_parameter_set_int()) with:- the AVS’ instance handle

- the component handle

- the parameter handle

- and (finally!) the new value.

Of course, a well-designed UI wouldn’t perform every one of these steps every time a parameter is changed. Instead it should keep around some inventory of handles for the current preset’s various components and parameters and only do the last step each time.

Parameters All the Way Down #

For the vast majority of effects this works well enough.

But there are some effects (currently around 8) which don’t have a fixed amount of parameters.

Some of their parameters are lists, i.e. a variable number of parameters of the same type.

For example in some effects you can define a list of colors that the rendered shapes will fade through over time.

By default it’s just one color, white, but you can add more.

But I just explained how an effect’s parameters are baked into the static AVS_Effect_Info struct at compile time.

How can this be changeable at runtime?

I could have designed the API to store parameter info with the components instead of statically with the effects. Then the component could just tell us which parameters there currently are and how many. But this would prevent a lot of the caching opportunities for consumers of the API. Keeping this information static is very neat and practical: Now an API user, like a UI, can just query all effects and parameter types at startup instead of having to go through the whole dance outlined above every time a parameter changes its value.

Fortunately these variable parameters are homogeneous lists where every entry is the same type. This makes it possible to statically define the type of the list entries and only defer discovering the length of the list at runtime. One additional indirection makes this system capable of storing almost arbitrarily complex data: Lists never contain the sub-type directly but a heterogeneous “collection” of child parameters, even if it’s just one — just as if it were a little effect itself with its own parameters.

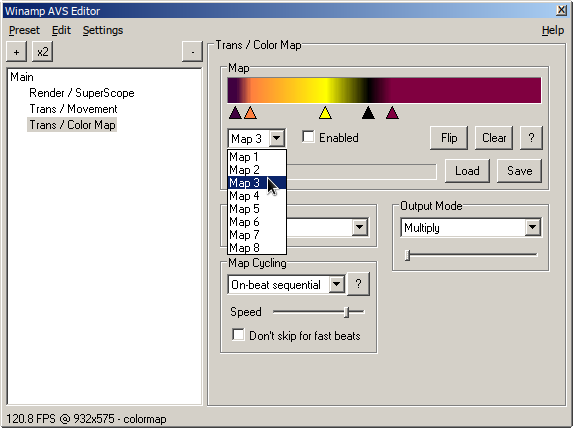

‘Color Map’, a very popular effect in AVS, is by far the most extensive use-case for parameter lists. Each of the 8 maps (itself a list of parameters, fixed-size for now) contains a nested list of colors defining the gradient of the map.

Okay, I admit this might be confusing at first glance, so let me try to illustrate: Let’s assume there’s an effect that wants to let the user define a gradient. (AVS actually does have an effect similar to this, it’s “Color Map”, see the illustration above.) What is a gradient? It’s a distribution of colors along a line, controlled by a few points of a known, fixed color, and a smooth interpolation in between. As you can see, each of these control points is defined by two values: Its color and its position along the line. Let’s look at a simple example gradient, from red to black, spanning the whole length of a line 100 units long:

- color: red

position: 0 - color: black

position: 99

We also want — just to keep it more interesting — to have a choice of linear or radial gradients.

Remember that what we want to achieve is a gradient configuration that happens to have two colors, but could have more or fewer. The effect for this may be defined (in the notation from above) like so:

name: BasicGradient

description: Draw a gradient.

handle: 111 # I picked easily recognizable handles.

parameters:

- name: Gradient

type: list

handle: 55555

min: 1 # Lists can specify how many items they may contain at least...

max: 100 # ... and at most. More than 100 colors is obviously useless.

children: # This is a special property for 'list' type parameters.

- name: Color

type: color

handle: 66666

- name: Position

type: int

handle: 77777

min: 0

max: 99

- name: Direction

type: select

handle: 88888

options: # And this is special for 'select' type parameters.

- Vertical

- Horizontal

- Radial

Notice how the Gradient parameter’s children property just defines the shape of one of the child parameters. This is all one can get out of the static information. API users will have to query the actual components at runtime to find out how many colors the gradient has.

Let’s look at a specific component of this type.

Note that while I do list parameters here, components don’t actually have a “parameter values” property.

You have to go through the chain

component → effect → parameters → type → get_int()/get_color()/etc.

to retrieve parameter values.

effect: 111 # = BasicGradient

handle: 1234567

parameter values:

Gradient:

length: 2

children:

- Color: red

Position: 0

- Color: black

Position: 99

Direction: Horizontal

The main visible difference is that we have two sets of color/position because this specific gradient consists of two colors. Secondly the color and position parameter values are two levels deep inside its parent “Gradient”, instead of just one. The first level constitute the two colors of the gradient and the second level the parameters in each item of that list. Only the second level was visible in the effect structure.

Parameter lists did complicate the code in some places quite a bit. But more significantly (again, a minimal API is key) it added 4 API endpoints and two optional arguments to every parameter editing function of the API. But it was necessary and the effect parameter system is much more expressive for it.

Working With List Items #

Any operation on a parameter within a parameter list requires a “path” into the parameter tree. Since parameter lists are just one level deep, with one exception (ColorMap) where it’s two levels, this path is always trivial: Just a list of one index (or in the case of ColorMap two) into the list.

For example to get the position of the second gradient control do this:

AVS_Handle avs;

AVS_Component_Handle component;

AVS_Parameter_Handle parameter_gradient_position;

// Initialize AVS, load the preset, find the component, and

// query its effect's parameters to find parameter_gradient_position

int64_t position_value = avs_parameter_get_int(

avs, component, parameter_gradient_position, 1, {1}

);

// position_value == 99

The last two arguments are a list of length 1, containing the index 1 for the second Gradient child.

The path along with the parameter handle for the Position sub-parameter is enough to uniquely identify the value.

Actions and On-Change-Handlers #

There is one other parameter type worth mentioning: action.

Action parameters are special because they don’t contain a value.

They are just triggers that an effect can define to run any code it wants.

This is useful for buttons in an effect UI that reset some state.

Or to apply the value of a different parameter (think file saving & loading) at a user-controlled time.

Setting a normal parameter value will always update that parameter in the effect’s internal configuration. But sometimes more complex things need to happen when a parameter value changes. A cache or buffer needs to be cleared or some internal value needs to be recalculated. To make this easy every parameter can have an on-change handler function attached (most parameters don’t). This function then gets run automatically when the value of a parameter is set through the API.

Parameter lists extend this concept and have three possible handlers: on-add, on-move, on-remove.

Note that these on-change handlers are not part of the API. Their existence is not exposed, it’s all internal to the parameter and its effect. It just bears mentioning here because it’s useful to know that changing a value may do more than just write some memory. Contrary to what the name suggests the handler function is also run if the value being set is not actually different from before. This can be helpful in edge cases or debugging, to have a way to just trigger the handler again.

A Dark Secret: Adding New List Items #

There is one part of the API I don’t like: avs_parameter_list_element_add().

As the name suggests it adds a new element to a parameter list.

The contained parameters should of course have values of the user’s choosing.

For example, adding a new color into the middle of the BasicGradient component from above should add a dark red at position 49.

A quick solution would have been to just grow the list and initialize it with some default values. Afterwards the values can be set through the normal parameter editing methods. This solution is awkward because of the handlers described above. Two types of handler functions would be run at separate times, first the list’s on-add handler and later the on-change handlers when setting the actual values. If the on-add handler moves the item around (e.g. if the list needs to be sorted) the case is completely hopeless because you’d have to rediscover your item in the list.

The only workable solution3 is to pass new values directly to avs_parameter_list_element_add().

This way all information is present at a single point and handlers get called when they need to.

But parameter values can have a variety of types and the C type system makes it difficult to define arguments without a fixed type.

The solution I chose was to introduce a union type which collects several types into one.

You then have to know the type of the parameter, to get the correct value out of the union again.

Unions can be unsafe to use and are not pretty to work with, but they are fairly common.

What’s worse though is that this could have also been a solution for the normal get and set operations on parameters.

The five different variants (currently) of getters and setters could have been one with a union value type.

But I still think dedicated methods for each type are a better way to go than unions.

What worries me is the potential for confusion when API users read down to the list-element-add part

and discover a different mechanism for doing essentially the same thing.

Current Status and Future Topics #

Since finishing the API draft I’ve been busy porting effects one-by-one to inherit from the new Effect class

which makes them support the editor API.

Currently around half of all the effect implementations have been changed.

Every now and then an effect has required some amendment to the API, but so far it has held up pretty well.

But the actual UI separation is not possible unless all are done!

So that final test is still pending…

In an upcoming post I will write a bit about how I’m porting the effects. After that I’ll talk about the basic API and possibly the C++ API wrapper I wrote to make the C API a bit more palatable.

Stay tuned!

-

In a nutshell, inheritance in object-oriented-programming language means the programmer defines a

classstructure for a common base concept and the classes inheriting from that base concept are specialized versions of that concept. A common example is a class “Animal” which may serve as parent to classes like “Dog” or “Cat”. ↩︎ -

The notation is based on YAML which you don’t really need to know about or understand to be able to read it. Just these two hints: List items are denoted by lines starting with a dash

-. Key/value maps are identified by blocks with the same indentation containingkey: value(key and value separated by a colon and a space). Example:

↩︎- item 1 - item 2 - key 1: value 1 key 2: value 2 key 3: - sub-item 1 - sub-item 2 - item 4 -

For a details about the alternatives I considered see the commit message introducing this change. ↩︎